At the intersections of African-American literature and diaspora studies, and with an eye toward the knotty entanglements of modern secularism and religion, I bring these interests together in my dissertation to trace out the literary genealogy of what I term “the godforsaken slave”—slaves who doubted in God’s all-loving, all-powerful nature because of the immense pain and suffering wrought under slavery (i.e. the problem of evil). Too often the popular antebellum image of the “pious slave”—naturally religious, perfectly devout—and its uncritical acceptance within humanities and social science scholarship, has obscured our understanding of early African-American Christianity and black diasporic faiths, even as others, more recently, have interpreted early black doubt, skepticism, and atheism as evidence of a black “secularization thesis” and secularism’s rise.

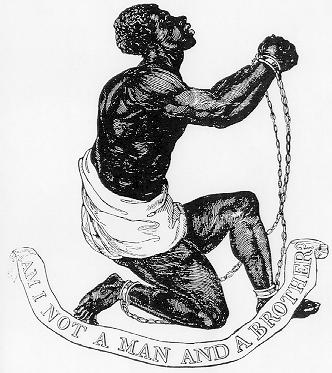

I cut against the grain of both, neither erasing the godforsaken slave’s crises of faith, nor mistaking them for secularism’s advent, reading them instead as protests against slavery’s faith-destroying powers in order to sway a culture increasingly worried over the loss of faith to abolish slavery for good, thereby resurrecting black faith, ironically, through dramatized scenes of godforsaken uncertainty and loss. Scouring thousands of antislavery sources—poetry, novels, slave narratives, newspapers, illustrations, sermons, songs, hymns, speeches, and more—across dozens of digital archives and online databases, I make a compelling case for the importance of “doubt” as an analytical framework in our literary scholarship, especially on race, politics, and the African diaspora.

Doubt, in other words, was a politically-generative argument for reclaiming black faith and freedom (not losing it), and has been ever since in the longue duree of African-American literary culture and in other circum-Atlantic contexts, finding expressions today in Ta-Nehisi-Coates’ Between the World and Me, Toni Morrison’s novel The Bluest Eye, and Kendrick Lamar’s Grammy album To Pimp a Butterfly. I, thus, offer a revisionary account of early black skepticism and faith in the Atlantic world, deconstructing the racially-fraught ways scholars have talked about black religion and injustice in the seismic wakes of the African diaspora and secular Enlightenment.

My book-length project The Godforsaken Slave will substantially expand my dissertation in different directions, chronologically (e.g. across the long 19th century, into the 20th century) and geographically (e.g. in transatlantic and global contexts), casting the godforsaken slave as a heuristic for interpreting the African diaspora, black religion, and secular modernity anew. Currently, I am just beginning to explore how writerly representations of black doubt, skepticism, and atheism in the circum-Atlantic world, namely relating to the problem of evil and divine injustice, often transcend the trope’s literary, existential, and political meanings in pre-Civil War America. I am, at the moment, scouring through Caribbean, “Black Atlantic,” Latino/a, British, and African writings to delineate these contours, which is turning out to be a fascinating project of archival excavation and insightful discovery on the long overlooked relationships between black secularism, slave religion, and the literature of slavery, transnationally and globally.